What is rage bait and why outrage has become a language of the internet

The term “rage bait” has been named the Oxford Word of the Year 2025, reflecting how outrage-driven content now shapes online conversations. As platforms increasingly reward emotional reactions, rage bait has moved from a niche tactic to a dominant online phenomenon. Qazinform News Agency examines what rage bait is, why it spreads so easily, and how it has evolved into both a tool for profit and a form of social interaction.

Rage bait refers to online content designed to provoke anger or outrage in order to boost engagement. It often relies on provocative headlines, exaggerated claims, or deliberately offensive opinions that push users to react emotionally rather than thoughtfully. Unlike traditional clickbait, which aims to spark curiosity, rage bait thrives on irritation, conflict, and polarisation.

According to Oxford University Press, this year’s choice for Word of the Year reflects a broader shift in how attention is captured online. Usage of the term tripled in 2025, showing both how common the tactic has become and how aware audiences are of its effects. Oxford Languages President Casper Grathwohl noted that while the internet once focused on curiosity, it now increasingly hijacks emotions, turning outrage into one of the strongest drivers of engagement.

But rage bait does not exist in only one form. To understand why it now dominates online spaces, it is important to look at how it is used intentionally, how it appears without intent, and how it has become normalised as part of digital culture.

Intentional rage bait and the money behind it

In 2025, intentional rage bait has become one of the most common content strategies on social media, largely because it is economically rewarded. Platforms monetise content based on engagement metrics - views, likes, replies, reposts, and comments - meaning posts that trigger anger or outrage often reach wider audiences than neutral or informational material. Studies and platform disclosures confirm that emotionally charged content consistently outperforms non-controversial posts in engagement.

A large-scale academic study analysing over 16,000 YouTube videos and 105 million comments found that controversial and toxic content generates significantly more user interaction than neutral material. Videos that attracted polarised or hostile comment sections saw spikes in replies and debate, which platforms interpret as indicators of success. While focused on YouTube, the study reflects engagement patterns on other major platforms where algorithms reward interaction.

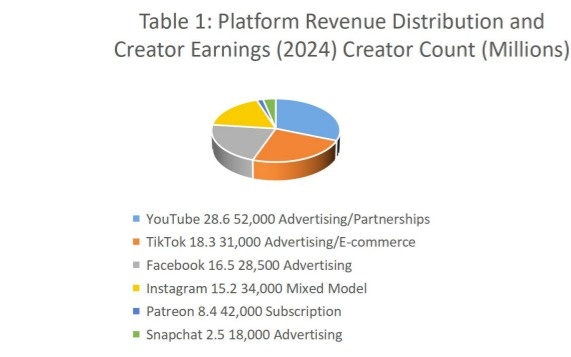

These engagement advantages translate into direct financial incentives. Around 28.6% of content creators list YouTube as their main income source, followed by TikTok at 18.3% and Facebook at 16.5%, according to creator-economy data. Only a small fraction earn thousands, while most make modest sums, meaning creators rely heavily on engagement to maximise revenue. In this system, controversy is a rational strategy rather than an accidental outcome.

Brands and influencers increasingly adopt similar tactics. Recent campaigns - such as Kim Kardashian’s $48 “face shapewear” promising targeted jawline compression and an American Eagle ad starring Sydney Sweeney explaining genetics before saying “My jeans are blue” - sparked backlash but achieved massive visibility. The outrage itself drove shares, comments, and free publicity, demonstrating that online criticism can function as marketing.

Platform policies further incentivise rage bait. Last year’s BBC report revealed that Meta executives acknowledged a rise in “engagement bait” on Threads, while X (formerly Twitter) updated its Creator Revenue Program to reward engagement from premium users regardless of content quality. As long as interaction drives payouts and visibility, rage bait remains a strategic and profitable tactic for creators and brands alike.

Unintentional rage bait and the risks of virality

Not all rage bait is created deliberately. Alongside intentional provocation, there is a growing presence of unintentional rage bait, where posts, videos, or comments trigger backlash without any intention to offend. This often happens when users share jokes, personal opinions, or trends without fully anticipating how they may be interpreted by wider or more polarised audiences.

A prominent example occurred during the 2022 FIFA World Cup, when a clip of a young Moroccan girl mocking Cristiano Ronaldo after Portugal’s loss went viral. Similar comments were made by other fans in a humorous context, but the girl became the main target of global backlash, particularly from football supporters. The reaction escalated quickly, resulting in online harassment and public debate about proportionality and responsibility.

This case shows how virality itself can transform harmless content into a source of outrage. Once detached from its original context, audiences often assign malicious intent that was never present. Algorithms then amplify the most emotional responses, spreading backlash faster than clarification or defence.

Unintentional rage bait also appears in everyday online communication. Users asking for advice or sharing personal experiences can trigger strong reactions from specific communities. In fast-moving digital spaces where nuance is limited, even ordinary posts can become flashpoints, turning everyday users into unexpected targets.

Rage bait as humour and online social interaction

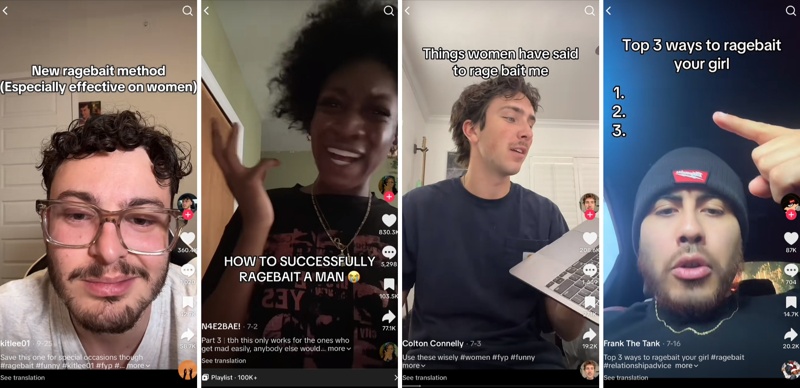

Beyond intention or impact, rage bait has increasingly become a form of online communication. Across platforms, users parody rage-inducing behaviour through skits, POV videos, and exaggerated influencer personas. These formats rely on shared context, where viewers understand the reference and the joke. Rage bait, in this sense, becomes a language rather than just a tactic.

(Video tags:1. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMDJa3KAo/ 2. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMDJaWLHy/ 3. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMDJaWkqV/ 4. https://vm.tiktok.com/ZMDJm6nqX/)

Rage bait is also used as social commentary. Many creators openly mock outrage culture by exaggerating its patterns or producing “tutorial-style” content on how to provoke reactions. These videos often attract high engagement, showing that audiences recognise and participate in the joke. Provocation itself becomes entertainment.

However, rage bait is not directed at one group alone. Online harassment campaigns frequently use rage-bait tactics to provoke, demean, and attack specific groups of people in social interactions. This shows that rage bait operates across multiple communities and power dynamics.

Even though the public tends to interact more with such content, the normalisation of rage bait as humour carries long-term risks. Repeated exposure to ironic outrage can desensitise audiences to degrading language and stereotypes. When harmful expressions are framed as jokes or trends, the boundary between satire and reinforcement weakens. As a result, rage bait is no longer only a reaction or a revenue tool - it is a shared social practice shaping how people interact, joke, argue, and attack online.

As Qazinform News Agency reported earlier, Dictionary.com selected the number “67” as its Word of the Year, while Cambridge Dictionary named parasocial its Word of the Year 2025.